Dr. Dorothy S. McClellan

GOODBYE TO POST-YUGOSLAVIA,

LONG LIVE THE CROATIAN STATE

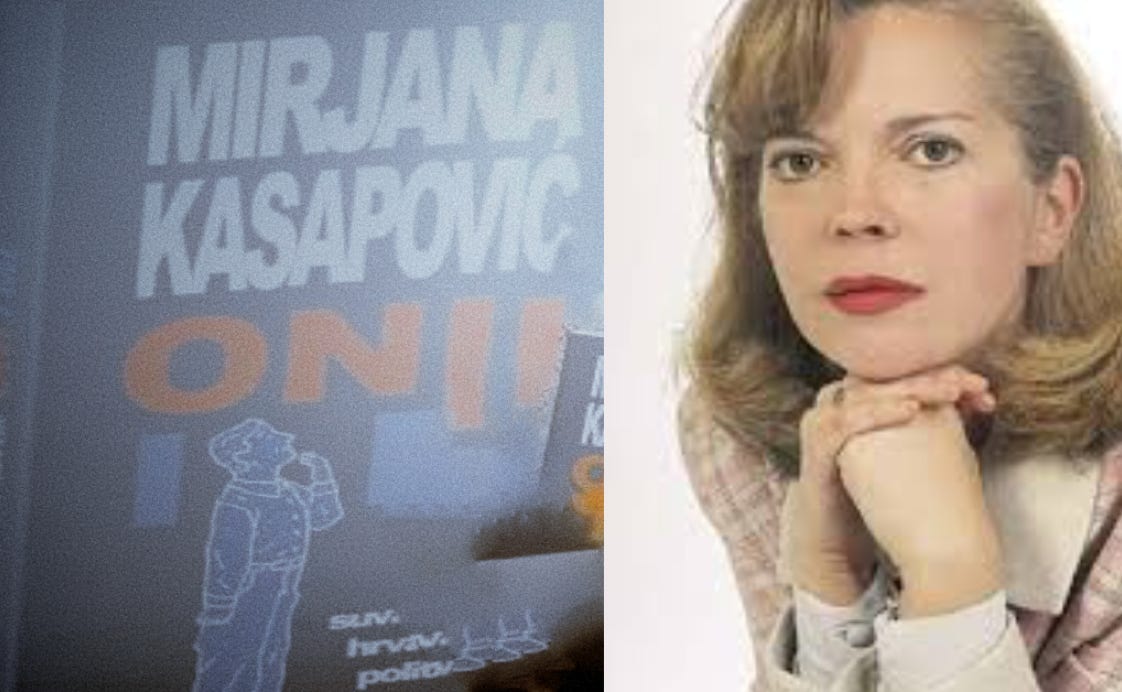

Mirjana Kasapović, a long-time full professor at the Faculty of Political Sciences in Zagreb, recently published a scientific paper in the Annals of the Croatian Political Science Society entitled “Goodbye to Post-Yugoslavia!” in which she explains with surgical precision why post-Yugoslavia was and remains an ideological construct that aims to preserve the name of Yugoslavia, using it to virtually operate with a non-existent state as something that is a political, cultural or social fact.

According to Kasapović, the ideological construct itself was tailored by the authors who came from the intellectual diaspora formed by the emigration of individuals from the countries created by the breakup of Yugoslavia, among whom some returned after the end of the wars to these areas and were employed at universities in the new countries. The narrative and discourse on post-Yugoslavism fragmented into different fields - literary, film, art, linguistic,

political, sociological, cultural, legal, etc. - and anchored in them.

“Post-Yugoslavian, as well as post-socialist, studies do not have their own subject of research. They are not focused on the real world but on ideologically constructed concepts. They are based on the territorial-political imagination. They overemphasize one (1990) at the expense of other fractures in the history of the peoples that made up Yugoslavia (1914, 1918, 1941, 1945), closing the political future of the new states to the old framework,” writes Professor Kasapović.

Among those post-Yugoslav studies that have acquired organizational and institutional forms, according to the author, are, among others, those published by the Center for Women’s Studies, the Center for Peace Studies, the Third Program of Croatian Radio, the Post-Yugoslav Peace Academy, Documenta, the House of Human Rights, and some magazines, newspapers and internet portals.

Kasapović states that some of their authors are conscious theoretical and ideological constructivists, while others are just professional epigones and opportunists or thoughtless followers and imitators of fashionable trends. Kasapović states that, admittedly, it is difficult to establish with absolute reliability how much post-Yugoslavism is the original product of that diaspora, and how much was imported from foreign, mainly American and British, political and scientific environments.

The Imposition of Western Narratives

The author of the paper further wonders if it would be meaningful to call the Kingdom of Yugoslavia a post-Habsburg and post-Ottoman state - nominally linking it to two centuries-old powerful empires that left deep cultural and social traces in the countries they ruled and to which many subjects of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia were emotionally attached. Why are the Czech Republic and Slovakia not called post-Czechoslovak states and why are there no post-Czechoslovak studies? And who will call Ukraine a post-Soviet country after the current war, just as Croatia and Bosnia and Herzegovina are called post-Yugoslav countries after the devastating wars of the nineties?

The imposition of Western narratives and discourses is, writes Kasapović, a form of intellectual and spiritual colonialism that many authors from the “scientific peripheries” accepted in order to be able to publish works in Western publications, which is one of the formal conditions of academic advancement.

Some parts of this article are quoted from a scientific paper: Kasapović, M. (2023). Goodbye to Post-Yugoslavia! Annals of the Croatian Political Science Society, 20(1).

Parts of quotes from Mirjana Kasapović’s work

“Goodbye to Post-Yugoslavia!”

“Yugoslavia was the most unsuccessful European state of the 20th century. There is no state in Europe that, in its seventy years of existence, from December 1918 to January 1992, was created twice and disintegrated twice in seas of blood of its citizens - in the world, interstate and civil wars of its “South Slavic tribes” and their “fraternal peoples and nationalities.”

The first Yugoslavia lasted less than 22 years, and the second less than 47 years - together they survived less than the average lifespan of European citizens.

All economic and political arrangements were tried to preserve that country: it was capitalist and socialist, monarchical and republican, unitary and federalist, pluralist and monistic, the king’s right-wing and the marshal’s left-wing dictatorship. It was in the West and the East, undecided and unaligned. Nothing helped.

It used the most violent methods of dealing with war enemies and political opponents. Yugoslav military forces killed hundreds of thousands of Croatian, Slovenian and other prisoners of war and civilians in Slovenia and Austria after the formal end of the war in 1945. This was not discussed in historiography and politics until the collapse of the state, partly because the state hid and erased the traces of its crimes, and because, through intimidation, it forced millions of inhabitants to remain silent - to live in a kind of schizophrenia in which they could not forget the past, and were not allowed to remember it.

It carried out massive ethnic cleansing of members of the German national minority in Vojvodina and Slavonia, expelling around half a million people. It applied retaliatory measures to the Italian minority in Croatia and Slovenia. When it finished the violent confrontations with the war enemies and their “servants,” it turned to the real and imaginary political enemies of the new government - clerofascists, Ibes, Hebrangs, Đilasovs, Rankovics, anarcho-liberals, Praxists, sixty-eighters, Maspokovs, unitarians, separatists, Islamists, etc. .- forcibly deporting them to islands with inhumane living conditions, sentencing them to multi-year prison sentences, persecuting them and their families, excommunicating them from public life. The secret services of the Yugoslav state killed dozens of political emigrants in assassinations and other terrorist methods around the world.

The attitude towards Slovenian, Macedonian and Albanian literature in these languages was a cultural derivative of the tacit political belief that the peoples of the “Serbo-Croatian” language constituted the political center, the core of the state, while the speakers of other languages lived on the political peripheries that were not equally constitutive for the state and, in the last resort, necessary for its survival.

It was considered that the “inferior periphery,” Macedonia, has no real interests and desire to separate from Yugoslavia, while without the “superior periphery,” Slovenia, even if it were to secede, Yugoslavia could still survive. Kosovo could always be pacified by force.

Therefore, the political animosities and defamatory methods of the post-Yugoslavs are directed mostly at Croatia, which they consider to be the most responsible for the breakup of Yugoslavia. Serbia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Montenegro, and North Macedonia did not really want that disintegration, and Slovenia could not independently and irrevocably cause it. If Croatia had not seceded, Yugoslavia would have survived.

Post-Yugoslav Studies Deal with the Study of “Post-Yugoslav Countries,” “Post-Yugoslav States” or “Post-Yugoslav Space”

Their authors came from the intellectual diaspora formed by the emigration of individuals from the countries created by the breakup of Yugoslavia in the wars of 1991-1995. and after their completion. Partly under the influence of its members - some of them returned and worked at universities in new countries - the narrative and discourse on post-Yugoslavism was also accepted by some other authors due to ideological and political beliefs, professional benefits, or intellectual convenience.

It is difficult to determine with complete reliability how much post-Yugoslavism is the original product of that diaspora, and how much was imported from foreign, mainly American and British, political and scientific environments.

In the unvarnished manifesto of the post-Yugoslav intellectual diaspora that systematically promotes post-Yugoslav studies, Dejan Jović (2003) explains the wartime, political, psychological, and professional circumstances in which it was created: “The disintegration of the state”, writes Jović (2003: 25), “is not only a question of passports, different definitions of citizenship, and the goal of political changes on a macro level, It touches groups and individuals, changing their identities. For all of us who lived through it, the disintegration of Yugoslavia, and especially the post-Yugoslav war, was that divisive event, due to which in many cases it is almost impossible to talk about the same life before and after it”. As they did not want to live in the post-Yugoslav states, some emigrated permanently or temporarily. “Some left simply because they believed that this was the only way they could preserve what they cared about - their own identity (which, especially among young and more educated people in Yugoslavia, could never be reduced to just national, i.e., ethnic identity), free life and free-thinking, the possibility to “remain yourself” (Jović, 2003: 26). Jović (2003: 26) calls those who chose that path “a new generation of young Yugoslavs and post-Yugoslavs,” who formed intellectually and politically after the breakup of Yugoslavia and in spite of it. Even thirty years after the formal breakup of Yugoslavia, Jović (2022) sees a “new generation of post-Yugoslavs”created as part of the unfinished “five-fold transition.”

It is not entirely clear how the new Yugoslavs differ from the post-Yugoslavs. The political and civic identity of both is actually virtual. it is not derived from belonging to a real but a fictional national or state community - it is an ideological construct par excellence. Both of them show a strong political, cultural, intellectual, and emotional attachment to the former Yugoslavia.

They do not want to “see” new independent states on their soil and call them post-Yugoslav states, post-Yugoslav countries, or post-Yugoslav space.

Post-Yugoslav studies ask a few simple questions: Why are contemporary political facts, such as the existence of new states, determined by a dead historical fact, such as Yugoslavia? Why are these mere post-Yugoslav states? Only because they were created after the dissolution of the SFRY, although some of them existed before the creation of the first Yugoslav state? Would it make sense to call the Kingdom of Yugoslavia a post-Habsburg and post-Ottoman state - nominally tying it to two centuries-old powerful empires that left deep cultural and social traces in the countries they ruled and to which many subjects of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia were emotionally attached? Or was the Kingdom of Yugoslavia a post-Serbian state? Why are the Czech Republic and Slovakia not called post-Czechoslovak states and why are there no post-Czechoslovak studies? Who still seriously calls Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania post-Soviet states?

And who will call Ukraine a post-Soviet country after the current war, just as Croatia and Bosnia and Herzegovina are called post-Yugoslav countries after the devastating wars of the nineties?

Post-Yugoslavism was and remains an ideological construct that aims to preserve the name Yugoslavia and use it to virtually operate with a non-existent state as something that is a political, cultural or social fact. Efforts to turn an ideological fiction into a political faction also gave birth to the naming of that fictional creation - it is called “post-Yugoslavia” (Abazović and Velikonja, 2014; Peruško, 2016; Babić, 2021).

What was unnamed, and seemed unnameable, was nevertheless given a bizarre name. The symbolic place of post-Yugoslavia used to be occupied by the region, but that was too general, conventional, and prosaic an expression.

The post-Yugoslav discourse therefore wants to replace the regionalist “performative discourse” in order to impose and legitimize a new determination of borders, create new mental images in people and manipulate them, and by means of its symbolic power and function build and destroy social groups and communities living in the respective space (Bourdieu, 1991: 220-221).

Post-Yugoslavia intentionally integrates different terms into a single name. In order for this creation to “come to life,” it is necessary, explicitly or implicitly, to intellectually deconstruct and de-subjectivize, and usually to politically denounce and demonize the states that exist on “its” soil, which have, so to speak, usurped it.

All Content © 2015 Croatian Film Institute, All Rights Reserved